Embedded systems are no longer “small computers with a single job.” Today’s edge devices run complex Linux stacks, multiple services, containerized workloads, and increasingly, AI pipelines. They process sensitive and mission-critical data locally, too often while being externally exposed by means of networks and in environments that are difficult to physically control.

As a result, the embedded security posture is shifting. Encrypting data at rest and data in transit remains necessary, but it is no longer sufficient. The biggest exposure is now the one that traditional encryption does not cover: data in use. The runtime is the new perimeter in embedded security.

The New Attack Surface: Sensitive Data While It Is Being Processed

If you encrypt storage, you prevent offline theft of data from disks or flash.

If you encrypt network traffic, you protect against interception and tampering in transit.

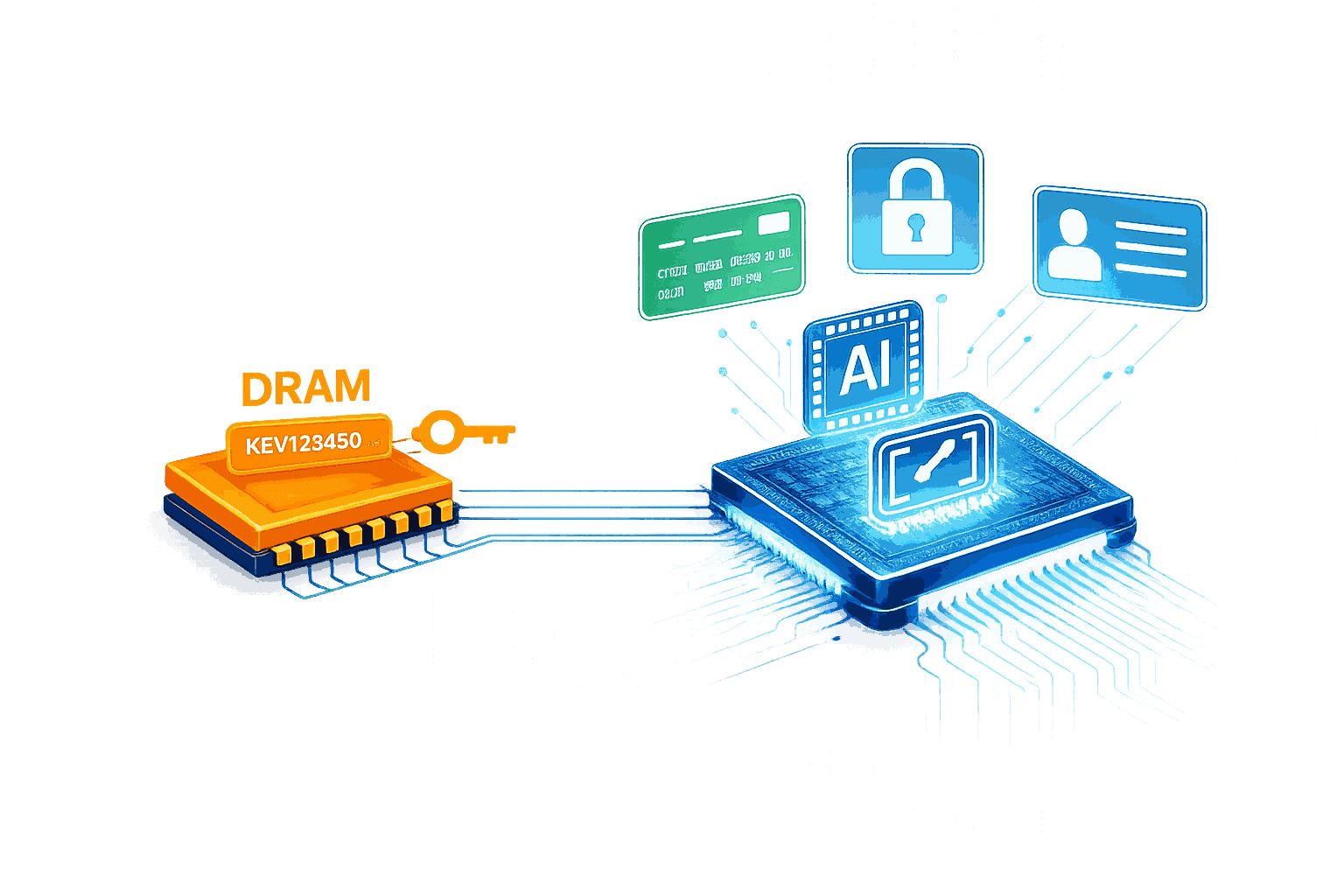

But at runtime, when an application decrypts secrets, performs a transaction, runs AI inference, or validates a credential, those sensitive assets must appear in plaintext somewhere: in CPU registers, in RAM, in caches, or inside shared system services.

This creates a blind spot that attackers increasingly exploit:

- Compromised OS or privileged services can inspect memory or hijack execution.

- Remote exploits and side-channel attacks can turn into credential theft and lateral movement.

- Debug interfaces and physical access can lead to runtime extraction of secrets.

- Supply-chain and update attacks can inject malicious code that targets in-memory data.

- Multi-service Linux deployments create opportunities for cross-application compromise.

In embedded Linux systems, the problem is amplified because the device often must remain connected and manageable, yet is deployed in the field for years. In practice, you cannot assume that the “general-purpose” part of the system will stay uncompromised forever.

So the question becomes: how do you protect sensitive workloads even if the rest of the device gets breached?

Confidential Computing at the Edge: Protecting “Data in Use”

Confidential computing addresses exactly this gap: isolate critical code and sensitive data into a protected execution environment, enforced by hardware- and software-based mechanisms with an extremely reduced Trusted Computing Base (TCB), not by the operating system itself. This is possible due to a pragmatic and practical observation: while the complexity of general-purpose software is ever increasing, that of security-critical software is increasing at a much lower pace.

In the cloud, this concept is commonly associated with hardware-enforced enclaves and TEEs. In embedded systems, the equivalent must be practical, lightweight, and compatible with real deployments, where you still need Linux flexibility, containerization, and performance.

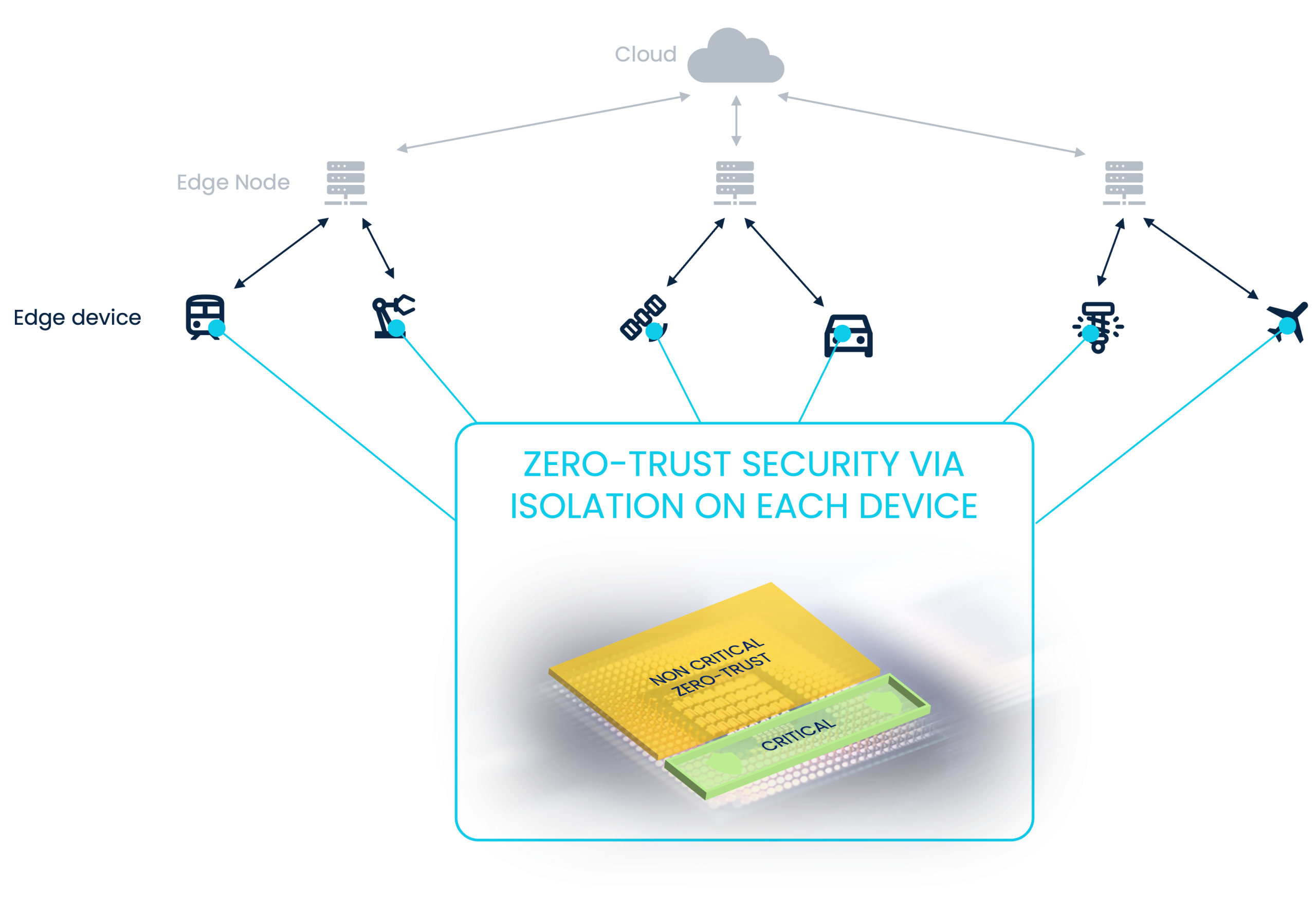

That’s why, for embedded Linux, confidentiality is not just about encryption—it is about strong runtime partitioning:

- keep exposed services (networking, UI, “non-critical” applications) in one space

- keep security-sensitive applications, secrets, and protected data processing in another one

- enforce isolation so that a breach in the open space does not become a breach of your crown jewelsvuluable secrets and IPs

This is where many embedded security designs struggle: implementing isolation is often complex, intrusive to existing workflows, or too expensive in performance.

A Pragmatic Path: Segregated Runtime Environments on Embedded Linux

Instead of asking teams to rewrite applications for an enclave model, an increasingly effective approach is to make isolation part of the runtime architecture, so developers can protect the critical components without touching their entire software stack.

This is the philosophy behind Accelerat Bunker for Linux, a software product designed to secure Linux applications on embedded devices with a dual-partition runtime model:

- Open World: a traditional, general-purpose Linux system that can remain externally exposed (network-connected, feature-rich, flexible).

- Bunker: a minimal, strongly isolated, security-hardened Linux execution environment for security-critical components.

This separation creates a simple but powerful security outcome: even if Open World is compromised, protected workloads and secrets inside the Bunker remain isolated—, reducing the chance of lateral movement and preventing access to sensitive data in use.

Why This Model Works Well for Embedded Systems

Embedded security has unique constraints: limited computationale resources, long device lifetimes, real-time requirements, and frequent use of third-party software. That’s why isolation needs to be:

- strong (hardware-assisted boundaries, not “best effort” sandboxing),

- compatible (work with Linux apps and container workflows),

- icremental (protect only what’s critical),

- cost-effective (avoid system-wide overhead),

- less patches (smaller TCB to maintain)

Bunker for Linux is built around these principles:

1) Strong isolation with minimal disruption

The partitioning between Open World and Bunker is based on hypervisor technology, isolating critical applications in a dedicated environment.

2) Security overhead only where it matters

You can enable resource-intensive countermeasures only for sensitive components inside the Bunker, while keeping performance high for everything else.

3) Hardened by design

The Bunker includes pre-installed and pre-configured hardening measures such as encrypted filesystem, attack detection and recovery, and countermeasures for side-channel attacks.

4) Built for real systems: containerization + secure updates

It includes support for containerization (e.g., Docker) and secure update procedures, both essential for real-world embedded product maintenance.

Reframing Embedded Threat Models with Bunker for Linux: Assume Breach, Protect What Matters

One of the biggest shifts in modern embedded security is adopting a zero-trust mindset on-device: assume that some parts of the system can be compromised and design them so that the impact is well controlled and confined.

Bunker for Linux explicitly aligns with this approach: it is designed so that even if Open World is breached, protected applications running within the Bunker are defended against unauthorized access and lateral movement.

In practical terms, that’s what “data in use” security should look like on embedded Linux:

- secrets never have to be exposed to the network-facing OS

- critical applications can run with higher guarantees of confidentiality and integrity

- compromise containment becomes an architectural feature, not an afterthought